In gu rês

John Yau

É preciso falar Singlish para expressar um sentimento singapurense.

Catherine Liu

Eu nunca aprendi singlês

Não sei falar taglês, mas já reconheci

as mudanças tonais de burrês, pobrês e mendiguês

Não sei in gu rês, mas vou estudá-lo por completo até seus

quebrados e queimados ossos.

Não sei in gu dwês, mas falo cágado e cagado

balela e gazela

Hoje falo barbacoa e canoa

Hoje falo cachorro covarde e cachorro amarelo

Não sei Spin Gloss, mas escuto forró e quiproquó,

negão e assombração

Não sei im bra vês, mas posso te dizer que meu sobrenome

consiste em três letras, e que tecnicamente todas são vogais

Eu não sei hum glês, mas sei comer com dois pauzinhos

Ah mas eu sei inglês porque o pai da minha mãe era inglês

e porque meu pai nasceu em 1921 em Nova York

e pôde retornar aos EUA em 1949

e virar um cidadão americano.

Eu não falar china, chanel, ou cheienes

Eu sei sim falar inglês porque sou capaz de avisar outras pessoas

de que eu não sou quem elas pensam que sou

Eu não sei chinês porque minha mãe disse que eu recusei a aprendê-lo

desde o meu nascimento, e que esta decisão

foi uma das maiores tristezas da sua vida

junto com o nascimento do meu irmão

Eu sei chinês sim porque entendi quando uma amiga de minha mãe disse

num domingo de manhã, logo depois de sentar-se para o chá:

“Espero que você não, mas estacionei meu helicóptero no seu telhado”

Porque eu não sei chinês fui avisado por um tradutor do espanhol

que isto significa que eu não sou chinês.

Ele disse que estudou chinês e, portanto, estava mais próximo

de ser chinês do que eu jamais poderia ser. Ninguém discordou dele publicamente

o que, de acordo com as regras do inglês, significa que ele está certo.

Eu sei inglês e sei que sabê-lo quer dizer

que nem sempre acredito nele.

O fato de eu discordar do tradutor do espanhol

é mais uma prova de que eu não sou chinês, pois os chineses

que moram nos EUA são sinceros e trabalhadores

e nunca discordariam de alguém que está certo.

Isto prova que eu sei até mesmo como me comportar em inglês.

Eu não sei inglês porque me divorciei e portanto

não devo ter entendido os votos que fiz no cartório.

Eu sei inglês porque da segunda vez que fiz um voto de casamento

tive de repeti-lo em hebraico.

Eu sei inglês porque sei o que “biscoito da sorte” quer dizer

quando dito em relação a uma mulher chinesa.

A autoridade em poesia anunciou que eu descobrira ser chinês

quando era vantajoso para mim fazê-lo.

Meu pai tinha medo de que se eu não falasse inglês corretamente

estaria condenado a trabalhar como garçom em um restaurante chinês.

Minha mãe, entretanto, disse que isto era impossível pois

eu não falava cantonês, e esta é a única língua

que os garçons de restaurantes chineses sabem falar.

Eu não sei nem cantonês nem inglês, an glo rês ou in gu rês.

An gús tiês é uma língua que todos podem falar, mas que ninguém escuta.

Eu sei falar inglês pois a mãe do meu pai era Ivy Hillier.

Ela nasceu e morreu em Liverpool depois de morar nos EUA e na China,

alegando ser descendente dos huguenotes.

Eu sei inglês porque não escutei minha avó direito e pensei

que ela disse sermos descendentes dos argonautas.

Eu sei inglês porque me lembro o que “made in japan” queria dizer

quando eu era criança.

Eu aprendo repetidas e repetidas vezes que não sei chinês.

Ontem um homem me perguntou como se escreve meu sobrenome em chinês,

pois tinha certeza que eu o pronunciava errado

e que se o meu pai pronunciara assim

o coitado se equivocou por toda a sua vida.

Eu não sei chinês muito embora meus pais conversassem em chinês diariamente

Eu sei inglês porque precisei pedir às enfermeiras para não colocarem minha mãe

em uma camisa de força, tranquilizando-as que eu me dispunha a esperar com ela

até o médico chegar na manhã seguinte.

Eu sei inglês porque saí do quarto quando o médico me disse

que eu não tinha por que estar ali.

Eu não sei chinês porque durante a guerra do Vietnam

me chamaram de “gook” ao invés de “chink” e eu percebi

que conseguia mudar de origem sem ter a intenção.

Eu não sei inglês porque quando meu pai disse que não queria

me ver nem morto, eu não soube exatamente o que ele quis dizer.

Eu não sei chinês porque nunca dormi com uma mulher

cuja vagina era puxada para o lado como os olhos da minha mãe.

Eu não sei nem inglês nem chinês e, talvez por isso,

não tenha colocado uma lápide no túmulo dos meus pais

pois senti que nenhuma língua refletia as que eles falavam.

Tradução: Marcelo Lotufo

Ing Grish

You need to speak Singlish to express a Singaporean feeling.

Catherine Liu

I never learned Singlish

I cannot speak Taglish, but I have registered

the tonal shifts of Dumglish, Bumglish, and Scumglish

I do not know Ing Grish, but I will study it down to its

black and broken bones.

I do not know Ing Gwish, but I speak dung and dungaree,

satrap and claptrap.

Today I speak barbecue and canoe

Today I speak running dog and yellow dog

I do not know Spin Gloss, but I hear humdrum and humdinger,

bugaboo and jigaboo

I do not know Ang Grish, but I can tell you that my last name

consists of three letters, and that technically all of them are vowels

I do not know Um Glish, but I do know how to eat with two sticks

Oh but I do know English because my father’s mother was English

and because my father was born in New York in 1921

and was able to return to America in 1949

and become a citizen

I no speak Chinee, Chanel, or Cheyenne

I do know English because I am able to tell others

that I am not who they think I am

I do not know Chinese because my mother said that I refused to learn it

from the moment I was born, and that my refusal

was one of the greatest sorrows of her life,

the other being the birth of my brother

I do know Chinese because I understood what my mother’s friend told her

one Sunday morning, shortly after she sat down for tea:

“I hope you don’t that I parked my helicopter on your roof.”

Because I do not know Chinese I have been told that means

I am not Chinese by a man who translates from the Spanish.

He said that he had studied Chinese and was therefore closer

to being Chinese than I could ever be. No one publicly disagreed with him,

Which, according to the rules of English, means he is right.

I do know English and I know that knowing it means

that I don’t always believe it.

The fact that I disagree with the man who translates from the Spanish

is further proof that I am not Chinese because all the Chinese

living in America are hardworking and earnest

and would never disagree with someone who is right.

This proves I even know how to behave in English.

I do not know English because I got divorced and therefore

I must have misunderstood the vows I made at City Hall.

I do know English because the second time I made amarriage vow

I had to repeat it in Hebrew.

I do know English because I know what “fortune cookie” means

when it is said of a Chinese woman.

The authority on poetry announced that I discovered that I was Chinese

when it was to my advantage to do so.

My father was afraid that if I did not speak English properly

I would be condemned to work as a waiter in a Chinese restaurant.

My mother, however, said that this was impossible because

I didn’t speak Cantonese, because the only language

waiters in Chinese restaurants know how to speak was Cantonese.

I do not know either Cantonese or English, Ang Glish or Ing Grish.

Anguish is a language everyone can speak, but no one listens to it.

I do know English because my father’s mother was Ivy Hillier.

She was born and died in Liverpool, after living in America and China,

and claimed to be a descendants of the Huguenots.

I do know English because I misheard my grandmother and thought

she said that I was a descendant of the Argonauts.

I do know English because I remember what “Made in Japan” meant

when I was a child.

I learn over and over again that I do not know Chinese.

Yesterday a man asked me how to write my last name in Chinese,

because he was sure that I had been mispronouncing it

and that if this was how my father pronounced it,

then the poor man had been wrong all his life.

I do not know Chinese even though my parents conversed in it every day.

I do know English because I had to ask the nurses not to put my mother

in a straitjacket, and reassure them that I would be willing to stay with her

until the doctor came the next morning.

I do know English because I left the room when the doctor told me

I had no business being there.

I do not know Chinese because during the Vietnam War

I was called a gook instead of a chink and realized

that I had managed to change my spots without meaning to.

I do not know English because when father said that he would

like to see me dead, I was never sure quite what he meant.

I do not know Chinese because I never slept with a woman

whose vagina slanted like my mother’s eyes.

I do not know either English or Chinese and, because of that,

I did not put a gravestone at the head of my parents’ graves

as I felt no language mirrored the ones they spoke.

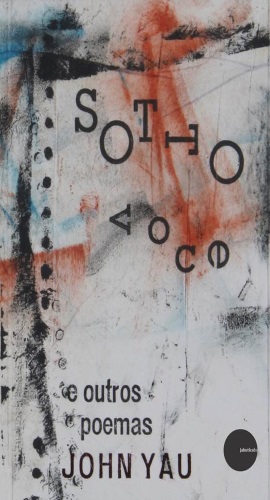

De Sotto Voce

e outros poemas

John Yau traduzido por Marcelo Lotufo

Mais informações em www.ediçõesjabuticaba.com.br