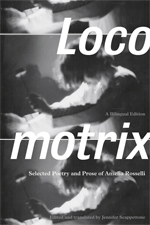

Locomotrix: Selected Poetry and Prose of Amelia Rosselli

Edited and translated and with an introduction by Jennifer Scappettone

University of Chicago Press, 2012

Half a century after the searching start—across and between tongues—of her uncompromising poetic practice, the poet Amelia Rosselli has emerged in global literary discussions as exemplary: as both prophetic and crucially contemporary. She has come to occupy a prominent position in literary history as one of the twentieth century’s most significant and demanding poets of the Italian language and beyond, with a body of work that concretizes in its agitation the postwar era’s fallout and bequest. Her books of poetry and recently collected prose are testaments to a uniquely multiform sincerity, and to a fiendishly restless mind, synthesizing a literary tradition that stretches from the thirteenth-century dolce stil novo through Rimbaud, Campana, Kafka, Joyce, and Pasternak with the frankness of the news. The daughter of an assassinated hero of the Italian Resistance who spent her childhood and adolescence in exile between France, England, and the United States before settling in Rome, Rosselli is esteemed for the idiolect she forged to voice the aftermath of this experience while resisting both the confessional first person dominating mainstream poetry during the years of her production and the aesthetic conformities of vanguardist schools. Self-described “poeta della ricerca” (“poet of research”), she regarded poetry as a sphere of activity exceeding the narcissistic gamut of self-expression and constraint of genteel intellectualism: language in Rosselli’s handling is a site of innovation with imperative philosophical and political consequences. Never mere linguistic exercise, her writing launches explicit and implicit structural assaults on the authority of traditional poetic forms, as well as the social and cognitive forms that gave rise to them.

She has fed me senseless small change, brought me to the bank, had me counted and found the sum surplus. —“My Clothes to the Wind” (1952)

To summarize her oeuvre, then, is but “an obligatory cruelty”; in its errancies, this work draws into question the synthetic categories of postwar poetry that have been forged thus far. In the early English prose piece called “My Clothes to the Wind,” the young author describes those who would encompass her as “Biscuit-makers all, and I a crumb who’d not coagulate,” voicing an attitude of alienation from reigning forms that would persist on many fronts. Rosselli’s tumultuous upbringing in the midst and aftermath of the Second World War as a victim of Fascism fostered her estrangement from the Italian literary establishment for decades. Being linguistically and culturally heterogeneous, her writing was initially regarded as a key exception to the rule of this national literature, even in the face of acclaim by prominent poet-critics and her historical distinction as the first—and still one of few—female Italian authors included in canon-defining anthologies of twentieth-century poetry. Yet as consciousness rises regarding the fundamental reciprocity between italianità (Italianness), emigration, and immigration, her poetic output has been subject to an explosion of attention. The impulses of Rosselli’s work in and against the Italian language are best appreciated when aligned with aesthetic trends that are international, while her role in shaping the future of this particular language and its literature is best grasped if we listen for the way it articulates the Italian patria, or “fatherland,” as itself a hybrid, transnational cultural formation. Rosselli’s is arguably the poetry most vital to evolving understandings of global modernism and postmodernism to have emerged from postwar Italy, testifying to the privations and hard-won inheritance of cultures bound by colossal networks of commerce and violence. Her poetic transmutes the war into which she was born into a battle against every species of tyranny: literary, cultural, sexual, economic, and, congenitally, political.

Rosselli was born in Paris in 1930 into a prominently, ardently antitotalitarian climate—into a family living in political exile. Her paternal grandmother and namesake, Amelia Pincherle Rosselli, was a secular Jewish Venetian feminist and republican thinker from a family active in the unification of Italy; Amelia Pincherle was the celebrated author of plays, some in Venetian dialect, and of short stories, children’s literature, political and literary essays, and translations. Amelia’s mother, Marion Catherine Cave, was a brilliant English activist of the Labour Party, from a family of Quaker and distant Irish Catholic heritage and modest means. Her father, Carlo Rosselli, was an intellectual leader and eventually a martyr of the anti-Fascist Resistance. Having been convicted—in a trial he exploited to critique Mussolini’s regime—of facilitating socialist Filippo Turati’s flight from Italy, Carlo himself escaped from the penal colony on the island of Lipari in 1929; Marion, pregnant with Amelia, was briefly arrested for complicity before the family was reunited in Paris. It was from the French capital that, with his brother Nello, Carlo launched Justice and Liberty, a prominent non-Marxist resistance movement based on principles of “liberal socialism,” which included Primo Levi, Cesare Pavese, and Leone Ginzburg among its affiliates, and later became the influential if short-lived Action Party. Upon the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Carlo was among the first to mobilize an armed brigade of volunteers in the fight against Franco, articulating the importance of organizing resistance to Fascism across Europe with the rallying cry “Today in Spain, tomorrow in Italy.” Identified as prime enemies of the regime, the Rosselli brothers were brutally murdered by the French Fascist terrorist organ La Cagoule in Bagnoles-de-l’Orne, Normandy in June 1937. The news was dealt to the seven-year-old “Melina” and her younger brother Andrea by their mother as a problem of language: “Do you know what the word assassination means?” She recalled in a 1987 interview, “We answered yes.”

—from the introduction by Jennifer Scappettone

from Variazioni belliche / Bellicose Variations (1964)

What ails my heart which beats so suavely

& maketh hee disconsolate, ese

soundings quite steel? lle Those

scomminglings therein ’mprinted fore Ille

be harrowed so

fiercely, alle hath evanished! O shhd mine

hares rampant thru th’nerves &s thru

channels rimed ’f thisse my lymph (o life!)

not stopp, thus yes, th’I, mio

nearyng unto mortae! In alle claundors soul of mine

thou dost propose a cure, thee I imbrace, you,—

find ’at Suave Word, you, return

to the comprehended saying that makes sure love remains.

from Documento / Document (1966-1973)

It comes

blown down the stairs,

likeness that I make of each thing

that passes through my mind

as if forgiveness were always at the ready there.

To barter the cigarettes of others

for a dormer full of good books . . .

In the court and the percentages I saw

the trial extended between the lines

and I acquitted the commanding officer

because you were the usual slaughterer

of women in the labyrinth

frightened by the scream

between mountains of stone

in the horror of a bomb

undetonated

like all of our best things:

politics in its chintzy sale

you bestow your assembled powers liberally

amongst the illiterate of the neighborhood

and amongst the dust you were carrying intact

in grey luggage.

•••

this is the sea today

in waves more serene that slash

that scream & that toil of yours deliberately

fusing the

vision of a gash with a gash

everything remakes itself,

& from the top & again

•••

the fragrant lymphatic canals

of mosquitoes

in the empty shack

no one can any longer lay hands on

knotty histories

trading them for a metaphor.

•••

There’s something like pain in this chamber, and

it is partly overcome: but the weight

of objects wins, their signifying

weight and loss.

There’s something like red in the tree, but it is

the orange of the lamp base

purchased in places I don’t wish to remember

because they also weigh.

Like nothing I can know of your hunger

the stylized fountains are

precise in wanting

a reversal can be settled of the destiny

of men divided by oblique noise.

General Strike 1969

lamps wholly alight and in the howl

of a calm audacious crowd

to find yourself there, acting with seriousness:

taking risks! May this apparent

childishness shatter even my own

power not to give a damn.

A deep inner God could have sufficed

my egotism did not suffice for me

the taste of riches in an otherwise

throttled revenge did not suffice

for these people. We had to

express something better: allow ourselves

this rhetoric that was a howl

of protest against undaunted

destruction in our frightened

houses. (I lost on my own that vertical

love of solitary god

revolutionizing myself in the people

removing myself from heaven.)