Susan Caldwell Gallery, October 8-29, 1983

Nielson Gallery, Boston, December 10, 1983 – January 7, 1984

Any painter worth their proverbial salt is forced to confront the relationship to their art. What does their art mean for them – into what realm of desire and fantasy and thought will it move?

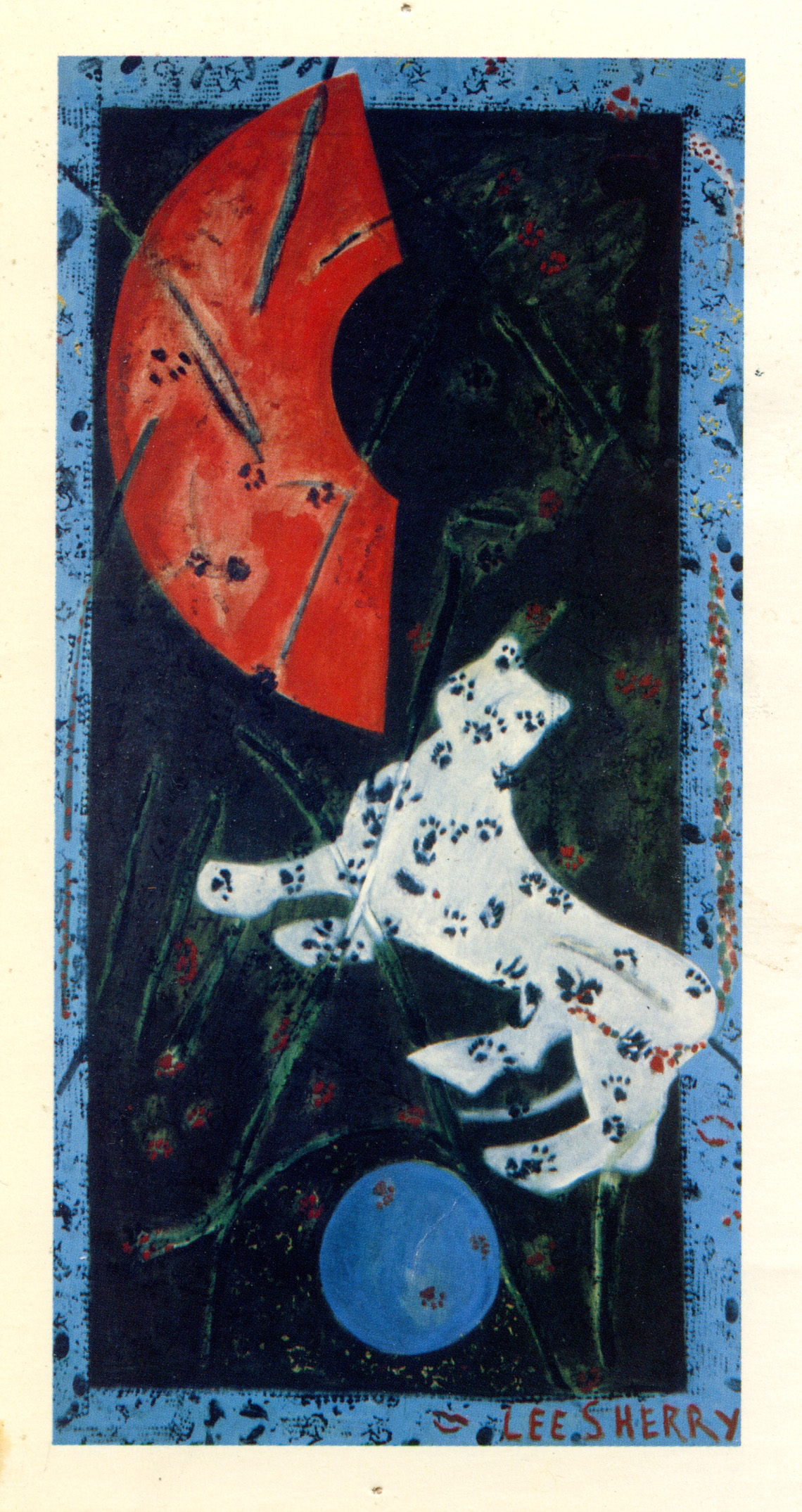

Lee Sherry’s latest paintings serve as a spatial magic carpet, an illusionistic space where phantasms of animals, threadlike lines, alphabets and words, broken patterns, and sheaths of color intersect, overlap, and meld. These paintings float and glisten delicately, luminously enveloping space. Strange animals melt, their gumdrop-like bodies suspended in the warmly colored, sticky paint glazes. The paintings reflect a meditative state of consciousness in which all is fluid and flux and the hardened state of the “facts” has not yet been perceived.

Into this most nebulous of realms, where association is paramount, Sherry has put her mark. She catches the paint while it moves in order to capture and hold the illuminated presences and characters of animals and other forms. This can happen only at the verge of the melting point in painting. By emphasizing neither the opacity of the paint nor the thick impasto now in common use, Sherry forces our attention to a netherworld of consciousness. Precise attention to detail and extensive use of glazes as well as the avoidance of harsh colors and thick paint distinguish her approach to the paint surface.

While Sherry’s earlier paintings were concerned with the opacity and dense texture of the paint surface her current paintings are full of translucent space and dense with references. Footprints, marks, birds, and letters form layers and tracks through the bounded space. At times birds appear below letters and overall color layers, at times they float up to the surface. Meanwhile a network or trace of 1ines weaves throughout the paintings – a system of dots and branches suggesting trails or roads in a spotted, starry sky. These lines are motifs carried over from earlier paintings. Sources of structural tension and opposition, they also serve as a link among different areas of the painting, a webbing or connecting thread.

Sherry sets up a hierarchy of forms in each painting, through repeated use of certain general motifs such as fans, animals circles, and lines. Elephants and other animals are likened to rectangles – they become geometric markings in space. Within a painting, the same image may be used in a large or small size – stressing a disjunction in scale and proportion as well as the imaginary nature of the iconography.

Animals other than humans are the primary symbolic forms of reference in these paintings. The human presence is indicated by an occasional handprint or footprint but most often by the presence of the alphabet – as well as by words and individual letters. Sherry makes literal use of the metaphor of painting as a form of visual writing or inscribing. Sometimes she incorporates nonsense syllables and often full-scale narratives or quoted passages.

Her inclusion of lettrist elements, both as fragments and wholes of meaning, brings the sphere of the human intellect, as narrative and symbol, into the strong context she has created of an animal-dominated world. Sherry’s pictures create a space in which nature and language achieve a unity. She emphasizes this point by incorporating both natural forms and letters in an allover glazed space of translucent unity – a possibly mystical fusion of the so-called “higher” and “lower” forms of life.

In Rara Avis (1983) a flock of stenciled birds in green, red, yellow, and blue fly in a reddish-pink glowing space flecked with irregular opaque white spots. Sherry first painted each bird, then poured the paint glaze over the whole, finally then reworking the birds. The interior of the composition is a vertical rectangle of words forming a scroll-like core. The English words from a Moroccan text speak of God’s protection from the deluge and the coming of a rainbow. The relationship between the narrow inner text and the wider outer border of birds in space makes use of the spatial conventions of Persian and Indian manuscripts. As in these manuscripts, the background motifs form a context for a denser inner core of words or images. In several other recent paintings Sherry has reversed this ordering making the writing form a border to the contained inner images.

Sherry uses repetition as a method of creating relationships among forms. To this end, she employs stencils of her own making as well as textile stamps to repeatedly print forms onto the linen. In this way, an analogy is drawn between linen and other fabrics by showing their common threadlike woven quality, shown also in the use of the textile patterns. The patterns she forms with her stencils and stamps, however, are frequently asymmetrical and altered or obscured.

These paintings are also strongly reminiscent of the prayer rugs that line the floors of mosques. The intricate patterns of these carpets yield a meditational meaning that serves as an earthbound cover for kneeling and praying in the vast space of the mosque. Islam, which shies away from the portrayal of the human figure in its religious art, does of course have a complex iconography of pattern and a traditional use of calligraphy as a decorative and meaning device. Sherry draws on these Islamic conventions while literally translating the language into the Roman alphabet.

Sharing Air (1983) is a small painting. The title refers to a scuba diving term for the extra underwater breathing apparatus that one diver carries to share with a diving partner in case of equipment trouble. In this painting, the inner core shape, which is often distinctly drawn in other works, melds with the outer atmosphere creating a shared space among the inner and outer forms. Sherry describes this painting as a place where eye (I) and the world come together. The painting encompasses and creates space – space is not blotted out. Once again, the technique of glazing and layering creates space among the denser marks allowing certain marks to reassert themselves against the veiling layers. There is an allover prismatic unity of splintered light and color.

Sherry’s images glisten and twinkle in the painted atmosphere in a manner similar to stars. The turbulent atmosphere of the multiple paint layers of glazes, which are cloudy, tinted and therefore not perfectly transparent, act as a kind of flexible lens. The turbulence of the painted space is the product of the constant irregular mixing of small regions of more and less dense paint layers. As a result, the refractive properties of the paint – its power to bend light one way or the other – are constantly changing and deflecting the line of sight. The glazes also create an overall space in which the sometimes more and sometimes less dense and opaque painted forms can momentarily loom forward in our sight or illusionistically pull our eyes backward into the spatial field.

————————————————————-

This 1983 review is published here for the first time.

See the Jacket2 obituary for Lee Sherry.

See also William Zimmer’s 1983 review in Arts.