Eu sou o tenebroso, – o viúvo, – o inconsolado

Príncipe d’Aquitânia, em triste rebeldia:

É morta a minha estrêla, – e no meu constelado

Alaúde há o negror, sol da melancolia.

Na noite tumular, em que me hás consolado,

O pausílipo, a Itália, o mar, a onda bravia,

Dá-me outra vez, – e dá-me a flor do meu agrado

E a ramada em que a rosa ao pâmpano se alia…

Sou Byron? Lusignan? Febo? O Amor? Advinha!

As faces me esbraseia o beijo da rainha:

Cismo e sonho na gruta em que a sereia nada…

Duas vêzes o Aqueronte, – é o grande feito meu, –

Transpus a modular, nesta lira de Orfeu,

Os suspiros da santa e os clamores da fada…

Tradução de Manuel Bandeira

Je suis le ténébreux, – le veuf, – l’inconsolé,

Le prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie:

Ma seule étoile est morte, – et mon luth constellé

Porte le soleil noir de la Mélancolie.

Dans la nuit du tombeau, toi qui m’as consolé,

Rends-moi le Pausilippe et la mer d’Italie,

La fleur qui plaisait tant à mon cœur désolé

Et la treille où le pampre à la rose s’allie.

Suis-je Amour ou Phébus?… Lusignan ou Biron?

Mon front est rouge encor du baiser de la reine;

J’ai rêvé dans la grotte où nage la sirène…

Et j’ai deux fois vainqueur traversé l’Achéron:

Modulant tour à tour sur la lyre d’Orphée

Les soupirs de la sainte et les cris de la fée.

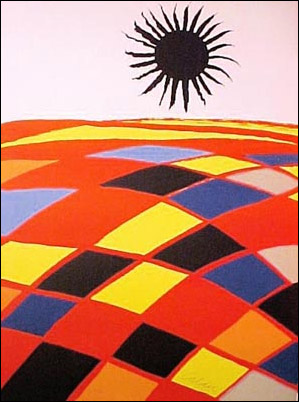

Soleil noir, Alexander Calder

Gérard de Nerval (May 22, 1808 – January 26, 1855) was the nom-de-plume of the French poet, essayist and translator Gérard Labrunie, the most essentially Romantic among French poets.

Two years after his birth in Paris, his mother died in Silesia whilst accompanying her husband, a military doctor, a member of Napoleon’s Grande Armée. He was brought up by his maternal great-uncle, Antoine Boucher, in the countryside of Valois at Mortefontaine. On the return of his father from war in 1814, he was sent back to Paris. He frequently returned to the countryside of the Valois on holidays and later returned to it in imagination in his Chansons et légendes du Valois.

His flair for translation was made manifest in his translation of Goethe’s Faust (1828), the work which earned him his reputation; Goethe praised it, and Hector Berlioz later used sections for his legend-symphony La Damnation de Faust. Other translations from Goethe followed; in the 1840s, Nerval’s translations introduced Heinrich Heine’s poems to French readers of the Revue des deux mondes. In the 1820s at college he became lifelong friends with Théophile Gautier and later joined Alexandre Dumas, père in the Petit Cénacle, in what was an exceedingly bohemian set, which was ultimately to become the Club des Hashischins. Nerval’s poetry breathes a Romantic deism, a sentient universe full of dream images and esoteric signs. His passion for the ‘spirit world’ was matched by a decidedly more negative view of the material one: “This life is a hovel and a place of ill-repute. I’m ashamed that God should see me here.” Among his admirers was Victor Hugo.

Gérard de Nerval’s first nervous breakdown occurred in 1841. In a series of novellas, collected as Les Illuminés, ou les précurseurs du socialisme (1852), on themes suggested by the careers of Rétif de la Bretonne, Cagliostro and others, he gave shape to feelings that followed his third attack of insanity. Increasingly poverty-stricken and disoriented, he finally committed suicide in 1855, hanging himself from a window grating. He left only a brief note to his aunt: “Do not wait up for me this evening, for the night will be black and white.” He was interred in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.