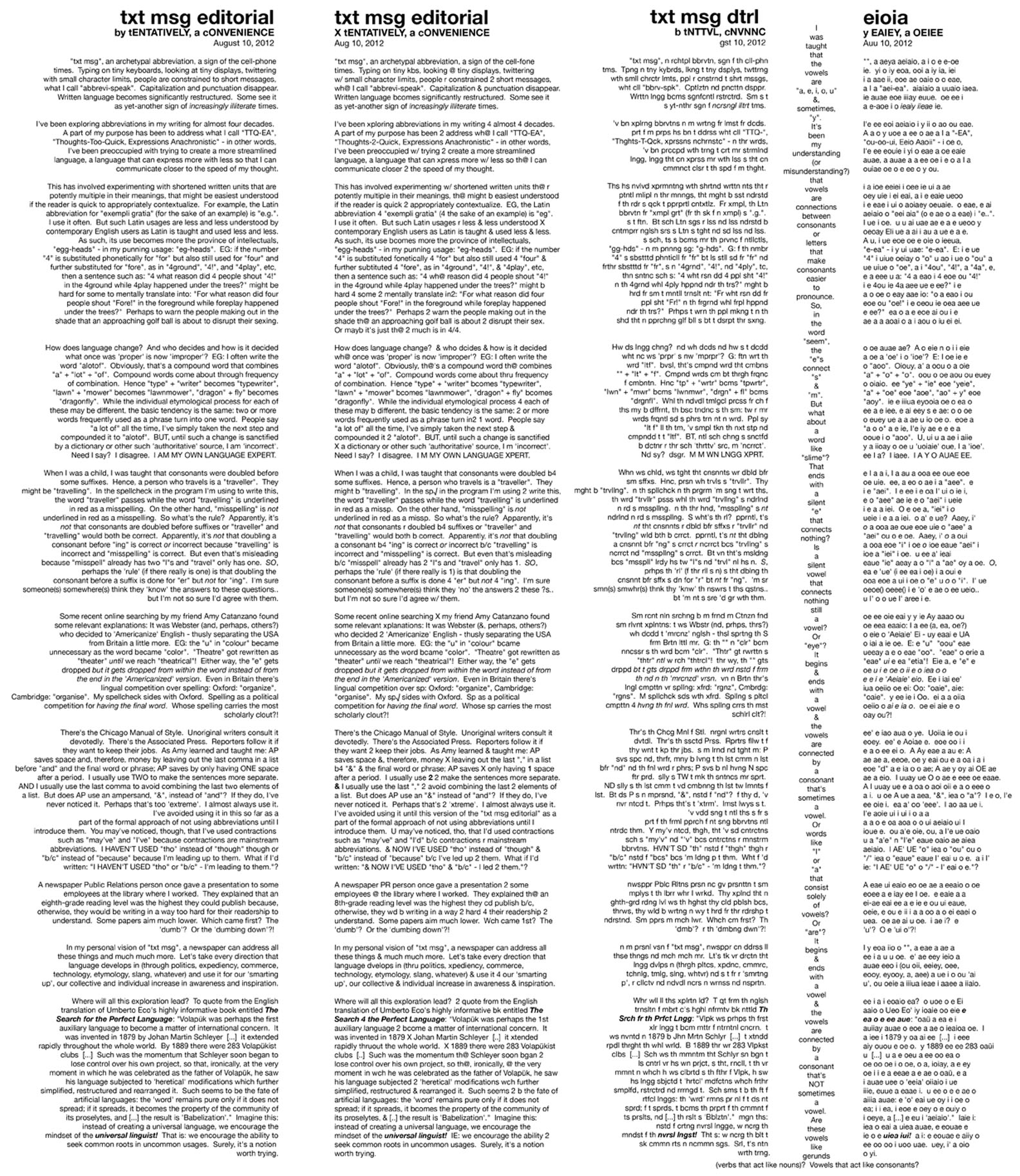

txt msg

editorial

by tENTATIVELY, a cONVENIENCE

August 10, 2012

“txt msg”, an archetypal abbreviation, a sign of the cell-phone times. Typing on tiny keyboards, looking at tiny displays, twittering with small character limits, people are constrained to short messages, what I call “abbrevi-speak”. Capitalization and punctuation disappear. Written language becomes significantly restructured. Some see it as yet-another sign of increasingly illiterate times.

I’ve been exploring abbreviations in my writing for almost four decades. A part of my purpose has been to address what I call “TTQ-EA”, “Thoughts-Too-Quick, Expressions Anachronistic” – in other words, I’ve been preoccupied with trying to create a more streamlined language, a language that can express more with less so that I can communicate closer to the speed of my thought.

This has involved experimenting with shortened written units that are potently multiple in their meanings, that might be easiest understood if the reader is quick to appropriately contextualize. For example, the Latin abbreviation for “exempli gratia” (for the sake of an example) is “e.g.”. I use it often. But such Latin usages are less and less understood by contemporary English users as Latin is taught and used less and less. As such, its use becomes more the province of intellectuals, “egg-heads” – in my punning usage: “eg-heads”. EG: if the number “4” is substituted phonetically for “for” but also still used for “four” and further substituted for “fore”, as in “4ground”, “4!”, and “4play”, etc, then a sentence such as: “4 what reason did 4 people shout “4!” in the 4ground while 4play happened under the trees?” might be hard for some to mentally translate into: “For what reason did four people shout “Fore!” in the foreground while foreplay happened under the trees?” Perhaps to warn the people making out in the shade that an approaching golf ball is about to disrupt their sexing.

How does language change? And who decides and how is it decided what once was ‘proper’ is now ‘improper’? EG: I often write the word “alotof”. Obviously, that’s a compound word that combines “a” + “lot” + “of”. Compound words come about through frequency of combination. Hence “type” + “writer” becomes “typewriter”, “lawn” + “mower” becomes “lawnmower”, “dragon” + fly” becomes “dragonfly”. While the individual etymological process for each of these may be different, the basic tendency is the same: two or more words frequently used as a phrase turn into one word. People say “a lot of” all the time, I’ve simply taken the next step and compounded it to “alotof”. BUT, until such a change is sanctified by a dictionary or other such ‘authoritative’ source, I am ‘incorrect’. Need I say? I disagree. I AM MY OWN LANGUAGE EXPERT.

When I was a child, I was taught that consonants were doubled before some suffixes. Hence, a person who travels is a “traveller”. They might be “travelling”. In the spellcheck in the program I’m using to write this, the word “traveller” passes while the word “travelling” is underlined in red as a misspelling. On the other hand, “misspelling” is not underlined in red as a misspelling. So what’s the rule? Apparently, it’s not that consonants are doubled before suffixes or “traveller” and “travelling” would both be correct. Apparently, it’s not that doubling a consonant before “ing” is correct or incorrect because “travelling” is incorrect and “misspelling” is correct. But even that’s misleading because “misspell” already has two “l”s and “travel” only has one. SO, perhaps the ‘rule’ (if there really is one) is that doubling the consonant before a suffix is done for “er” but not for “ing”. I’m sure someone(s) somewhere(s) think they ‘know’ the answers to these questions.. but I’m not so sure I’d agree with them.

Some recent online searching by my friend Amy Catanzano found some relevant explanations: It was Webster (and, perhaps, others?) who decided to ‘Americanize’ English – thusly separating the USA from Britain a little more. EG: the “u” in “colour” became unnecessary as the word became “color”. “Theatre” got rewritten as “theater” until we reach “theatrical”! Either way, the “e” gets dropped but it gets dropped from within the word instead of from the end in the ‘Americanized’ version. Even in Britain there’s lingual competition over spelling: Oxford: “organize”, Cambridge: “organise”. My spellcheck sides with Oxford. Spelling as a political competition for having the final word. Whose spelling carries the most scholarly clout?!

There’s the Chicago Manual of Style. Unoriginal writers consult it devotedly. There’s the Associated Press. Reporters follow it if they want to keep their jobs. As Amy learned and taught me: AP saves space and, therefore, money by leaving out the last comma in a list before “and” and the final word or phrase; AP saves by only having ONE space after a period. I usually use TWO to make the sentences more separate. AND I usually use the last comma to avoid combining the last two elements of a list. But does AP use an ampersand, “&”, instead of “and”? If they do, I’ve never noticed it. Perhaps that’s too ‘extreme’. I almost always use it. I’ve avoided using it in this so far as a part of the formal approach of not using abbreviations until I introduce them. You may’ve noticed, though, that I’ve used contractions such as “may’ve” and “I’ve” because contractions are mainstream abbreviations. I HAVEN’T USED “tho” instead of “though” though or “b/c” instead of “because” because I’m leading up to them. What if I’d written: “I HAVEN’T USED “tho” or “b/c” – I’m leading to them.”?

A newspaper Public Relations person once gave a presentation to some employees at the library where I worked. They explained that an eighth-grade reading level was the highest they could publish because, otherwise, they would be writing in a way too hard for their readership to understand. Some papers aim much lower. Which came first? The ‘dumb’? Or the ‘dumbing down’?!

In my personal vision of “txt msg”, a newspaper can address all these things and much much more. Let’s take every direction that language develops in (through politics, expediency, commerce, technology, etymology, slang, whatever) and use it for our ‘smarting up’, our collective and individual increase in awareness and inspiration.

Where will all this exploration lead? To quote from the English translation of Umberto Eco’s highly informative book entitled The Search for the Perfect Language: “Volapük was perhaps the first auxiliary language to become a matter of international concern. It was invented in 1879 by Johan Martin Schleyer […] it extended rapidly throughout the whole world. By 1889 there were 283 Volapükist clubs […] Such was the momentum that Schleyer soon began to lose control over his own project, so that, ironically, at the very moment in which he was celebrated as the father of Volapük, he saw his language subjected to ‘heretical’ modifications which further simplified, restructured and rearranged it. Such seems to be the fate of artificial languages: the ‘word’ remains pure only if it does not spread; if it spreads, it becomes the property of the community of its proselytes, and […] the result is ‘Babelization’.” Imagine this: instead of creating a universal language, we encourage the mindset of the universal linguist! That is: we encourage the ability to seek common roots in uncommon usages. Surely, it’s a notion worth trying.

txt msg

editorial

X tENTATIVELY, a cONVENIENCE

Aug 10, 2012

“txt msg”, an archetypal abbreviation, a sign of the cell-fone times. Typing on tiny kbs, looking @ tiny displays, twittering w/ small character limits, people r constrained 2 short messages, wh@ I call “abbrevi-speak”. Capitalization & punctuation disappear. Written language bcomes significantly restructured. Some see it as yet-another sign of increasingly illiterate times.

I’ve been xploring abbreviations in my writing 4 almost 4 decades. A part of my purpose has been 2 address wh@ I call “TTQ-EA”, “Thoughts-2-Quick, Expressions Anachronistic” – in other words, I’ve been preoccupied w/ trying 2 create a more streamlined language, a language that can xpress more w/ less so th@ I can communicate closer 2 the speed of my thought.

This has involved experimenting w/ shortened written units th@ r potently multiple in their meanings, th@ might b easiest understood if the reader is quick 2 appropriately contextualize. EG, the Latin abbreviation 4 “exempli gratia” (4 the sake of an example) is “eg”. I use it often. But such Latin usages r less & less understood X contemporary English users as Latin is taught & used less & less. As such, its use bcomes more the province of intellectuals, “egg-heads” – in my punning usage: “eg-heads”. EG: if the number “4” is substituted fonetically 4 “for” but also still used 4 “four” & further subtituted 4 “fore”, as in “4ground”, “4!”, & “4play”, etc, then a sentence such as: “4 wh@ reason did 4 people shout “4!” in the 4ground while 4play happened under the trees?” might b hard 4 some 2 mentally translate in2: “For what reason did four people shout “Fore!” in the foreground while foreplay happened under the trees?” Perhaps 2 warn the people making out in the shade th@ an approaching golf ball is about 2 disrupt their sex. Or mayb it’s just th@ 2 much is in 4/4.

How does language change? & who dcides & how is it decided wh@ once was ‘proper’ is now ‘improper’? EG: I often write the word “alotof”. Obviously, th@’s a compound word th@ combines “a” + “lot” + “of”. Compound words come about thru frequency of combination. Hence “type” + “writer” bcomes “typewriter”, “lawn” + “mower” bcomes “lawnmower”, “dragon” + fly” bcomes “dragonfly”. While the individual etymological process 4 each of these may b different, the basic tendency is the same: 2 or more words frequently used as a phrase turn in2 1 word. People say “a lot of” all the time, I’ve simply taken the next step & compounded it 2 “alotof”. BUT, until such a change is sanctified X a dictionary or other such ‘authoritative’ source, I m ‘incorrect’. Need I say? I disagree. I M MY OWN LANGUAGE XPERT.

When I was a child, I was taught that consonants were doubled b4 some suffixes. Hence, a person who travels is a “traveller”. They might b “travelling”. In the sp√ in the program I’m using 2 write this, the word “traveller” passes while the word “travelling” is underlined in red as a missp. On the other hand, “misspelling” is not underlined in red as a missp. So what’s the rule? Apparently, it’s not that consonants r doubled b4 suffixes or “traveller” and “travelling” would both b correct. Apparently, it’s not that doubling a consonant b4 “ing” is correct or incorrect b/c “travelling” is incorrect and “misspelling” is correct. But even that’s misleading b/c “misspell” already has 2 “l”s and “travel” only has 1. SO, perhaps the ‘rule’ (if there really is 1) is that doubling the consonant before a suffix is done 4 “er” but not 4 “ing”. I’m sure someone(s) somewhere(s) think they ‘no’ the answers 2 these ?s.. but I’m not so sure I’d agree w/ them.

Some recent online searching X my friend Amy Catanzano found some relevant xplanations: It was Webster (&, perhaps, others?) who decided 2 ‘Americanize’ English – thusly separating the USA from Britain a little more. EG: the “u” in “colour” bcame unnecessary as the word bcame “color”. “Theatre” got rewritten as “theater” until we reach “theatrical”! Either way, the “e” gets dropped but it gets dropped from within the word instead of from the end in the ‘Americanized’ version. Even in Britain there’s lingual competition over sp: Oxford: “organize”, Cambridge: “organise”. My sp√ sides with Oxford. Sp as a political competition for having the final word. Whose sp carries the most scholarly clout?!

There’s the Chicago Manual of Style. Unoriginal writers consult it devotedly. There’s the Associated Press. Reporters follow it if they want 2 keep their jobs. As Amy learned & taught me: AP saves space &, therefore, money X leaving out the last “,” in a list b4 “&” & the final word or phrase; AP saves X only having 1 space after a period. I usually use 2 2 make the sentences more separate. & I usually use the last “,” 2 avoid combining the last 2 elements of a list. But does AP use an “&” instead of “and”? If they do, I’ve never noticed it. Perhaps that’s 2 ‘xtreme’. I almost always use it. I’ve avoided using it until this version of the “txt msg editorial” as a part of the formal approach of not using abbreviations until I introduce them. U may’ve noticed, tho, that I’d used contractions such as “may’ve” and “I’d” b/c contractions r mainstream abbreviations. & NOW I’VE USED “tho” instead of “though” & “b/c” instead of “because” b/c I’ve led up 2 them. What if I’d written: “& NOW I’VE USED “tho” & “b/c” – I led 2 them.”?

A newspaper PR person once gave a presentation 2 some employees @ the library where I worked. They explained th@ an 8th-grade reading level was the highest they cd publish b/c, otherwise, they wd b writing in a way 2 hard 4 their readership 2 understand. Some papers aim much lower. Wch came 1st? The ‘dumb’? Or the ‘dumbing down’?!

In my personal vision of “txt msg”, a newspaper can address all these things & much much more. Let’s take every drection that language dvelops in (thru politics, xpediency, commerce, technology, etymology, slang, whatever) & use it 4 our ‘smarting up’, our collective & individual increase in awareness & inspiration.

Where will all this exploration lead? 2 quote from the English translation of Umberto Eco’s highly informative bk entitled The Search 4 the Perfect Language: “Volapük was perhaps the 1st auxiliary language 2 bcome a matter of international concern. It was invented in 1879 X Johan Martin Schleyer [..] it xtended rapidly thruout the whole world. X 1889 there were 283 Volapükist clubs [..] Such was the momentum th@ Schleyer soon bgan 2 lose control over his own project, so th@, ironically, @ the very moment in wch he was celebrated as the father of Volapük, he saw his language subjected 2 ‘heretical’ modifications wch further simplified, restructured & rearranged it. Such seems 2 b the fate of artificial languages: the ‘word’ remains pure only if it does not spread; if it spreads, it bcomes the property of the community of its proselytes, & [..] the result is ‘Babelization’.” Imagine this: instead of creating a universal language, we encourage the mindset of the universal linguist! IE: we encourage the ability 2 seek common roots in uncommon usages. Surely, it’s a notion worth trying.

txt msg

dtrl

b tNTTVL, cNVNNC

gst 10, 2012

“txt msg”, n rchtpl bbrvtn, sgn f th cll-phn tms. Tpng n tny kybrds, lkng t tny dsplys, twttrng wth smll chrctr lmts, ppl r cnstrnd t shrt mssgs, wht cll “bbrv-spk”. Cptlztn nd pncttn dsppr. Wrttn lngg bcms sgnfcntl rstrctrd. Sm s t s yt-nthr sgn f ncrsngl lltrt tms.

‘v bn xplrng bbrvtns n m wrtng fr lmst fr dcds. prt f m prps hs bn t ddrss wht cll “TTQ-“, “Thghts-T-Qck, xprssns nchrnstc” – n thr wrds, ‘v bn prccpd wth trng t crt mr strmlnd lngg, lngg tht cn xprss mr wth lss s tht cn cmmnct clsr t th spd f m thght.

Ths hs nvlvd xprmntng wth shrtnd wrttn nts tht r ptntl mlipl n thr mnngs, tht mght b sst ndrstd f th rdr s qck t pprprtl cntxtlz. Fr xmpl, th Ltn bbrvtn fr “xmpl grt” (fr th sk f n xmpl) s “.g.”. s t ftn. Bt sch Ltn sgs r lss nd lss ndrstd b cntmprr nglsh srs s Ltn s tght nd sd lss nd lss. s sch, ts s bcms mr th prvnc f ntllctls, “gg-hds” – n m pnnng sg: “g-hds”. G: f th nmbr “4” s sbstttd phnticll fr “fr” bt ls stll sd fr “fr” nd frthr sbstttd fr “fr”, s n “4grnd”, “4!”, nd “4ply”, tc, thn sntnc sch s: “4 wht rsn dd 4 ppl sht “4!” n th 4grnd whl 4ply hppnd ndr th trs?” mght b hrd fr sm t mntll trnslt nt: “Fr wht rsn dd fr ppl sht “Fr!” n th frgrnd whl frpl hppnd ndr th trs?” Prhps t wrn th ppl mkng t n th shd tht n pprchng glf bll s bt t dsrpt thr sxng.

Hw ds lngg chng? nd wh dcds nd hw s t dcdd wht nc ws ‘prpr’ s nw ‘mprpr’? G: ftn wrt th wrd “ltf”. bvsl, tht’s cmpnd wrd tht cmbns “” + “lt” + “f”. Cmpnd wrds cm bt thrgh frqnc f cmbntn. Hnc “tp” + “wrtr” bcms “tpwrtr”, “lwn” + “mwr” bcms “lwnmwr”, “drgn” + fl” bcms “drgnfl”. Whl th ndvdl tmlgcl prcss fr ch f ths my b dffrnt, th bsc tndnc s th sm: tw r mr wrds frqntl sd s phrs trn nt n wrd. Ppl sy “lt f” ll th tm, ‘v smpl tkn th nxt stp nd cmpndd t t “ltf”. BT, ntl sch chng s snctfd b dctnr r thr sch ‘thrttv’ src, m ‘ncrrct’. Nd sy? dsgr. M M WN LNGG XPRT.

Whn ws chld, ws tght tht cnsnnts wr dbld bfr sm sffxs. Hnc, prsn wh trvls s “trvllr”. Thy mght b “trvllng”. n th spllchck n th prgrm ‘m sng t wrt ths, th wrd “trvllr” psss whl th wrd “trvllng” s ndrlnd n rd s msspllng. n th thr hnd, “msspllng” s nt ndrlnd n rd s msspllng. S wht’s th rl? pprntl, t’s nt tht cnsnnts r dbld bfr sffxs r “trvllr” nd “trvllng” wld bth b crrct. pprntl, t’s nt tht dblng a cnsnnt bfr “ng” s crrct r ncrrct bcs “trvllng” s ncrrct nd “msspllng” s crrct. Bt vn tht’s msldng bcs “msspll” lrdy hs tw “l”s nd “trvl” nl hs n. S, prhps th ‘rl’ (f thr rll s n) s tht dblng th cnsnnt bfr sffx s dn for “r” bt nt fr “ng”. ‘m sr smn(s) smwhr(s) thnk thy ‘knw’ th nswrs t ths qstns.. bt ‘m nt s sre ‘d gr wth thm.

Sm rcnt nln srchng b m frnd m Ctnzn fnd sm rlvnt xplntns: t ws Wbstr (nd, prhps, thrs?) wh dcdd t ‘mrcnz’ nglsh – thsl sprtng th S frm Brtn lttl mr. G: th “” n “clr” bcm nncssr s th wrd bcm “clr”. “Thtr” gt rwrttn s “thtr” ntl w rch “thtrcl”! thr wy, th “” gts drppd bt t gts drppd frm wthn th wrd nstd f frm th nd n th ‘mrcnzd’ vrsn. vn n Brtn thr’s lngl cmpttn vr spllng: xfrd: “rgnz”, Cmbrdg: “rgns”. M spllchck sds wth xfrd. Spllng s pltcl cmpttn 4 hvng th fnl wrd. Whs spllng crrs th mst schlrl clt?!

Thr’s th Chcg Mnl f Stl. nrgnl wrtrs cnslt t dvtdl. Thr’s th ssctd Prss. Rprtrs fllw t f thy wnt t kp thr jbs. s m lrnd nd tght m: P svs spc nd, thrfr, mny b lvng t th lst cmm n lst bfr “nd” nd th fnl wrd r phrs; P svs b nl hvng N spc ftr prd. slly s TW t mk th sntncs mr sprt. ND slly s th lst cmm t vd cmbnng th lst tw lmnts f lst. Bt ds P s n mprsnd, “&”, nstd f “nd”? f thy d, ‘v nvr ntcd t. Prhps tht’s t ‘xtrm’. lmst lwys s t. ‘v vdd sng t n ths s fr s prt f th frml pprch f nt sng bbrvtns ntl ntrdc thm. Y my’v ntcd, thgh, tht ‘v sd cntrctns sch s “my’v” nd “‘v” bcs cntrctns r mnstrm bbrvtns. HVN’T SD “th” nstd f “thgh” thgh r “b/c” nstd f “bcs” bcs ‘m ldng p t thm. Wht f ‘d wrttn: “HVN’T SD “th” r “b/c” – ‘m ldng t thm.”?

nwsppr Pblc Rltns prsn nc gv prsnttn t sm mplys t th lbrr whr I wrkd. Thy xplnd tht n ghth-grd rdng lvl ws th hghst thy cld pblsh bcs, thrws, thy wld b wrtng n wy t hrd fr thr rdrshp t ndrstnd. Sm pprs m mch lwr. Whch cm frst? Th ‘dmb’? r th ‘dmbng dwn’?!

n m prsnl vsn f “txt msg”, nwsppr cn ddrss ll thse thngs nd mch mch mr. Lt’s tk vr drctn tht lngg dvlps n (thrgh pltcs, xpdnc, cmmrc, tchnlg, tmlg, slng, whtvr) nd s t fr r ‘smrtng p’, r cllctv nd ndvdl ncrs n wrnss nd nsprtn.

Whr wll ll ths xplrtn ld? T qt frm th nglsh trnsltn f mbrt c’s hghl nfrmtv bk nttld Th Srch fr th Prfct Lngg: “Vlpk ws prhps th frst xlr lngg t bcm mttr f ntrntnl cncrn. t ws nvntd n 1879 b Jhn Mrtn Schlyr […] t xtndd rpdl thrght th whl wrld. B 1889 thr wr 283 Vlpkst clbs […] Sch ws th mmntm tht Schlyr sn bgn t ls cntrl vr hs wn prjct, s tht, rncll, t th vr mmnt n whch h ws clbrtd s th fthr f Vlpk, h sw hs lngg sbjctd t ‘hrtcl’ mdfctns whch frthr smplfd, rstrctrd nd rrrngd t. Sch sms t b th ft f rtfcl lnggs: th ‘wrd’ rmns pr nl f t ds nt sprd; f t sprds, t bcms th prprt f th cmmnt f ts prslts, nd […] th rslt s ‘Bblztn’.” mgn ths: nstd f crtng nvrsl lngge, w ncrg th mndst f th nvrsl lngst! Tht s: w ncrg th blt t sk cmmn rts n ncmmn sgs. Srl, t’s ntn wrth trng.

I was taught that the vowels are “a, e, i, o, u” &, sometimes, “y”. It’s been my understanding (or misunderstanding?) that vowels are connections between consonants or letters that make consonants easier to pronounce. So, in the word “seem”, the “e”s connect “s” & “m”. But what about a word like “slime”? That ends with a silent “e” that connects nothing? Is a silent vowel that connects nothing still a vowel? Or “eye”? It begins & ends with a vowel & the vowels are connected by a consonant that’s sometimes a vowel. Or words like “I” or “a” that consist solely of vowels? Or “are”? It begins & ends with a vowel & the vowels are connected by a consonant that’s NOT sometimes a vowel. Are these vowels like gerunds (verbs that act like nouns)? Vowels that act like consonants?

eioia

y EAIEY, a OEIEE

Auu 10, 2012

“”, a aeya aeiaio, a i o e e-oe ie. yi o iy eoa, ooi a iy ia, iei i a aae ii, eoe ae oaie o o eae, a I a “aei-ea”. aiaiaio a uuaio iaea. ie auae eoe iiiay euue. oe ee i a e-aoe i o ieaiy iieae ie.

I’e ee eoi aeiaio i y ii o ao ou eae. A a o y uoe a ee o ae a I a “-EA”, “ou-oo-ui, Eeio Aaoii” – i oe o, I’e ee eouie i yi o eae a oe eaie auae, a auae a a ee oe i e o a I a ouiae oe o e ee o y ou.

i a ioe eeiei i oee ie ui a ae oey uie i ei eai, a i e eaie ueoo i e eae i ui o aoiaey oeuaie. o eae, e ai aeiaio o “eei aia” (o e ae o a eae) i “e..”. I ue i oe. u u ai uae ae e a e ueoo y oeoay Eli ue a ai i au a ue e a e. A u, i ue eoe oe e oie o ieeua, “e-ea” – i y ui uae: “e-ea”. E: i e ue “4” i uiue oeiay o “o” u ao i ue o “ou” a ue uiue o “oe”, a i “4ou”, “4!”, a “4a”, e, e a eee u a: “4 a eao i 4 eoe ou “4!” i e 4ou ie 4a aee ue e ee?” i e a o oe o eay aae io: “o a eao i ou eoe ou “oe!” i e oeou ie oea aee ue e ee?” ea o a e eoe ai ou i e ae a a aoai o a i aou o iu ei ei.

o oe auae ae? A o eie n o i i eie a oe a ‘oe’ i o ‘ioe’? E: I oe ie e o “aoo”. Oiouy, a’ a oou o a oie “a” + “o” + “o”. oou o oe aou ou euey o oiaio. ee “ye” + “ie” eoe “yeie”, “a” + “oe” eoe “aoe”, “ao” + y” eoe “aoy”. ie e iiiua eyooia oe o ea o ee a e iee, e ai eey s e ae: o o oe o euey ue a a ae u io oe o. eoe a “a o o” a e ie, I’e iy ae e e e a ooue i o “aoo”. U, ui u a ae i aiie y a iioay o oe u ‘uoiaie’ oue, I a ‘ioe’. ee I a? I iaee. I A Y O AUAE EE.

e I a a i, I a au a ooa ee oue eoe oe uie. ee, a eo o ae i a “aee”. e i e “aei”. I e ee i e oa I’ ui o ie i, e o “aee” ae ie e o “aei” i ueie i e a a iei. O e oe a, “iei” i o ueie i e a a iei. o a’ e ue? Aaey, i’ o a ooa ae oue eoe uie o “aee” a “aei” ou o e oe. Aaey, i’ o a oui a ooa eoe “i” i oe o ioe eaue “aei” i ioe a “iei” i oe. u ee a’ ieai eaue “ie” aeay a o “l” a “ae” oy a oe. O, ea e ‘ue’ (i ee ea i oe) i a oui e ooa eoe a ui i oe o “e” u o o “i”. I’ ue oeoe() oeee() i e ‘o’ e ae o ee ueio.. u I’ o o ue I’ aree i e.

oe ee oie eai y y ie Ay aaao ou oe eea eaaio: I a ee (a, ea, oe?) o eie o ‘Aeiaie’ Ei – uy eaai e UA o iai a ie oe. E: e “u” “oou” eae ueeay a e o eae “oo”. “eae” o erie a “eae” ui e ea “etia”! Eie a, e “e” e oe u i e oe o ii e o iea o o e e i e ‘Aeiaie’ eio. Ee i iai ee’ iua oeiio oe ei: Oo: “oaie”, aie: “oaie”. y ee ie i Oo. ei a a oiia oeiio o ai e ia o. oe ei aie e o oay ou?!

ee’ e iao aua o ye. Uoiia ie ou i eoey. ee’ e Aoiae e. eoe oo i i e a o ee ei o. A Ay eae a au e: A ae ae a, eeoe, oe y eai ou e a oa i a i eoe “d” a e ia o o ae; A ae y oy ai OE ae ae a eio. I uuay ue O o ae e eee oe eaae. A I uuay ue e a oa o aoi oii e a o eee o a i. u oe A ue a aea, “&”, iea o “a”? I e o, I’e ee oie i. ea a’ oo ‘eee’. I ao aa ue i. I’e aoie ui i ui i o a a a a o e oa aoa o o ui aeiaio ui I ioue e. ou a’e oie, ou, a I’e ue oaio u a “a’e” n “I’e” eaue oaio ae aiea aeiaio. I AE’ UE “o” iea o “ou” ou o “/” iea o “eaue” eaue I’ eai u o e. a i I’ ie: “I AE’ UE “o” o “/” – I’ eai o e.”?

A eae ui eaio eo oe ae a eeaio o oe eoee a e iay ee I oe. e eaie a a ei-ae eai ee a e ie e ou ui eaue, oeie, e ou e ii i a a oo a o ei eaei o uea. oe ae ai u oe. i ae i? e ‘u’? O e ‘ui o’?!

I y eoa iio o “”, a eae a ae a ee i a u u oe. e’ ae eey ieio a auae eeo i (ou oii, eeiey, oee, eooy, eyooy, a, aee) a ue i o ou ‘ai u’, ou oeie a iiiua ieae i aaee a iiaio.

ee i a i eoaio ea? o uoe o e Ei aaio o Ueo Eo’ iy ioaie oo eie e ea o e ee aue: “oaü a ea e i auiiay auae o eoe a ae o ieaioa oe. I a iee i 1879 y oa ai ee […] i eee aiy ouou e oe o. y 1889 ee ee 283 oaüi u […] u a e oeu a ee oo ea o oe oo oe i o oe, o a, ioiay, a e ey oe i i e a eeae a e ae o oaü, e a i auae uee o ‘eeia’ oiiaio i ue iiie, euue a eaae i. u ee o e e ae o aiiia auae: e ‘o’ eai ue oy i i oe o ea; i i ea, i eoe e oey o e ouiy o i oeye, a […] e eu i ‘aeiaio’.” Iaie i: iea o eai a uiea auae, e eouae e ie o e uiea iui! a i: e eouae e aiiy o ee oo oo i uoo uae. uey, i’ a oio o yi.