HUSH AND TRAVAIL

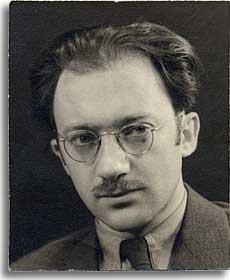

IN MEMORY ABRAHAM SUTZKEVER

(JULY 15, 1913 – JANUARY 20, 2010)

Abraham Sutzkever Selected Poetry and Prose, translated from the Yiddish by Barbara and Benjamin Harshav, with an Introduction by Benjamin Harshav (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991)

Abraham Sutzkever—who died early this year on January 20th at the age of 96—was, as The New York Times obituary mentioned, one of “the great Yiddish poets of his generation.” But to describe him in only that way is to miss much of his larger contribution to literary history. Indeed, as Benjamin Harshav begins his Introduction to Sutzkever: Life and Poetry, “Sutzkever is one of the great poets of the twentieth century.” Harshav adds:

I do not say this lightly. He is not a philosophical poet; there was

no sophisticated philosophy in Jewish culture. Nor is he a descriptive

poet; the language of Modernism was opposed to description, and

the fictional worlds of Sutzkever’s poetry are presented through ev-

ocation and allusion rather than direct statement. But the language of

his poetry—the profound sound orchestration and the metaphorical

and mythopoeic imagery—is as dense, unmediated, and suggestive

as that in the poetry of Mandelstam or Rilke. And his responses to

historical reality are as sharp as any in the verse of Brecht. The para-

doxical amalgam of these two extremes of twentieth-century poetry—

self-focused poetic language and ideological engagement—is successful

in Sutzkever’s work because both are presented through the events of

the poet’s own biography.

And what a biography that was! Born in 1913 in Smorgoń, Lithuania, southwest of Vilna, Sutzkever and his family were forced during his second year of birth to leave the city with all other Jews within twenty-four hours, after which the city was burned to the ground, the Russian high command fearing them as German “spies.”

Through connections with other travelers, the Sutzkevers ended up in Omsk in western Siberia, where Abraham lived until seven years of age, when his father died of heart failure. The brutally cold, but spectacularly beautiful landscape, would haunt Sutzkever’s poetry for the rest of his life, resulting in what he himself described as “the snow-sounds falling in my head,” and expressed most powerfully in poems such as “Frozen Jews”:

They come over me, blue bones in a row—

Frozen Jews over plains of snow.

With the end of the Russian Civil War, Sutzkever’s mother Reine returned to Lithuania with her three children, settling in Vilna. During those same years, Vilna became a center for Jewish and Yiddish-language activities. For generations since the fourteenth century, Jews had migrated into the area around Vilna until by the eighteenth century this last pagan country in Europe became one of the most important centers for Jewish learning in the world. Although the actual population of Jewish citizens in Vilna was small (at the beginning of World War II, 60,000 Jews lived in the city, with refugees from Poland adding another 20,000 more) as Harshav makes clear,”the area it dominated was immense.”

People would come from surrounding towns and villages to trade

or study and return to their hometowns or move to the West, and

still be proud of their “Vilna” origins. The parents of the Vilna Gaon;

the Haskalah historian of Vilna, Rashi Fin; the founders of YIVO

(Yiddish Scientific Institute), Max Weinreich and Zelig Kalmanovich;

the Yiddish poet Sutzkever and the Hebrew poet Abba Kovner; and

the Polish poets Michiewicz and Milosz were not born in Vilna itself,

though their names are linked with that cultural center. Jerusalem of

Lithuania was the symbolic focus and aristocratic pride of a vast,

extraterritorial Jewish empire.

Even as a thirteen year-old in Vilna, Sutzkever began writing poetry, first in Hebrew and then—influenced, in part, by the Yiddish linguist and YIVO director, Max Weinreich— in Yiddish. Self-taught, the young Abraham even attempted poetry in Old Yiddish and translated the Yiddish romance Bove Bukh, written in Venice in 1508. Joining the Vilna Jewish scouts’ Di Bin (the Bee) Sutkever dedicated himself, like his fellow scouts, to guard secular Yiddish culture. A close friendship with Miki Chernikhov (whose family read Evgeny Onegin) introduced the young Abrasha to other Russian Symbolist poets, Edgar Allen Poe and the Polish Romantic poets such as Cyprian Norwid. One might describe this brief period as a “ecstatic” time. As Sutzkever described just such activities in his Ecstasies:

When with eyes shut

I wrote a poem, suddenly

My hand got burned,

And when I started

From that black fire,

The paper breathed

A name like a lily: God.

But my pen, in awe and wonder,

Crossed out the word

And wrote instead

A more familiar word: Man.

Since then, a voice unheard

Haunts me like an unseen bird

That pecks, pecks at my soul’s door:

—Is that what you traded me for?

Sutkever’s group of friends, known as “The Young Vilna Group,” included the American Yiddish novelist Joseph Opatoshu, Shmerke Katcherginsky, painter Ben-Zion Michtom, Y. Opatoshu, Chiam Grade, Elchonon Vogler, Moshe Levin, Peretz Mirasky, Shimshon Kaban, and Leyzer Volf. Sutkever’s first book was published by the Yiddish Writers’ Union in Warsaw, and in 1940, his important book of poetry, Vladiks (From the Forest), was published in Lithuania.

In September 1939, soon after Sutzkever’s marriage, Poland was divided between Germany and the Soviet Union, the Russians entering Vilna, arresting many Jewish leaders, and turning over the city to independent Lithuania, who renamed the city Vilnius.

On June 22, 1941 the Germans attacked, occupying Vilna two days later. Immediately over 100,000 Jews of the region were liquidated, and those 20,000 left were crammed into a Vilna ghetto of only seven streets. Daily, Jewish men were arrested off the streets and taken to camps or swept into forced labor. Sutzkever hid in his mother’s Snipishok apartment, for weeks living in a crawl space under the house’s roof. His wife Freydke, having heard of a search for him, came to take him away, but he could not even walk. Soon after, however, he joined Jewish worker brigades, hiding in various spots. But on September 5, 1941 he and two others were captured by the Lithuanians, forced to dig their graves, and were about to be shot. Their countrymen, however, intentionally aimed over their heads, secreting them to hiding places in the ghetto. There Sutzkever rejoined his mother and wife. Having to flee one ghetto for another, he left his mother in a hiding place, but when he returned to free her, she was gone, the location having been discovered and its inhabitants taken off. Freydke, meanwhile, bore their son in the Ghetto hospital, an act that was forbidden; the Germans poisoned the child.

Joining a group of intellectuals who worked each day outside the ghetto at the YIVO building, Sutzkever was set to work on cataloguing the books assembled by the Germans on Jewish history, and designating the most important works for shipment to Germany. Sutzkever and his friends, however, secretly smuggled hundreds of these rare books into the ghetto, burying them. Many of these materials later made it to Moscow or were uncovered in Vilna after the War, with help from Sutzkever and others.

It was also at YIVO where Sutzkever was smuggled his first machine gun, and later, along with his wife and Shmerke Katcherginsky, he left the ghetto upon the ghetto uprising, joining the partisans led by Zelda, who led forays from the surrounding forests. Here the most physically able fought on, while women and children were abandoned in the ghetto to die or lived in the forests, left to their own devices. Sutzkever and Katcherginsky were assigned to write the brigade’s history. Soon thereafter, Russian writer Ilya Ehrenburg arranged for the Sutzkevers’ rescue by plane:

When they finally reached the other partisan brigade, a small

plane landed on the ice-covered lake. Sutzkever sat in its

opening, with Freydke tied to his knees, and two more partisans

were stuck in the rear. The plane veered though the heavy fire

of the German front, diving suddenly, and eventually emerging

on the Soviet side.

“If I didn’t write, I wouldn’t live,” announced Sutzkever in a 1985 New York Times interview. “When I was in the Vilna ghetto, I believed, as an observant Jew believes in the Messiah, that as long as I was writing, was able to be a poet, I would have a weapon against death.”

In all of Sutzkever’s writing, accordingly, there is the spectre of horror, the fear of destruction simultaneously at moments of peace and great beauty.

From the Forest

Of grass and flowers, the substance dissolves

Into drops of dew.

And he who wants can see

The subtle play

Of black and fire, silver and blue.

All around,

Trees sleep, sprawling on the ground,

Their shadows grow high.

The air is cool and soft

As dry

Water.

Silent, calm,

Mute paths kiss.

Here-and-there,

Green glows wink at you.

A nest trembles,

A spring shines.

You see:

Worlds spin on their axes

And dews are mirrors for the cosmos

If someone screamed right now,

All the skies would dissolve

In cosmic panic.

But all is hush. Just shadows

Cast by the spirited nightingale:

Following the star notes, he reveals

His lonely night

And his travail.

Los Angeles, May 9, 2010