Bobby—

All is forgiven!

As soon as you’re ready to come out of your room

We will be there to listen.

–Your fickle listeners

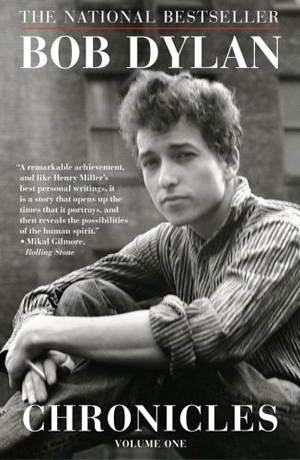

Bobby Zimmerman done good. From 1962, when, at the age of 22 he invented himself as Bob Dylan, and for the next 13 years, ending with one his many masterpieces, Blood on the Tracks, when he was 35, he wrote ’n’ sung some of the most remarkable, buoyant, an’ expansive works in the history of American song. Yet Dylan reached his apogee just two years after Blood on the Tracks, with his unredeemably lost album (which he called, without evident irony, Saved). And now, or anyway a couple of years back, Dylan has released the first volume of what may be an ongoing memoir. The book attempts to grapple with what made those 13 years possible and also what happened after. Yet, from the point of view of dealing with what happened after 1975, the book is a strategic failure, since Dylan has about as much critical distance on himself as a trapeze artist in a lion’s den. But then, the moral of his take is that there is, indeed, no failure like success.

Dylan’s Chronicles invites a new, longer view of his vexed work, as a singer-songwriter and also as a cultural figure. Dylan’s book is designed, in part, to warp and perhaps avert readymade contexts. But it also calls to mind contexts that are not available within the stock frames of “Behind the Music” that Dylan rails against, teases, but to which he ultimately succumbs.

Dylan’s Chronicles could be described as Melville’s Confidence Man meets Fellini’s 8½, with a touch of Garbo Speaks! (or possibly Harpo Speaks!). Flashes of brilliant let-me-do-th’talkin’ prose sparkles amidst a bevy nameless wives and named producers. (I find myself particular attracted to the way Dylan cuts off the “ly” from the end of adverbs.) This is a funny, often witty, Great Adventure (a.k.a. picaresque tale), whose featured character plays, at times, the role of the Unhappy Camper: Paul Rubens might well be the ideal choice to play the lead in the movie version: my privacy was stolen! But for all the fun and local color, the book has the perfume of deep sadness fused with confusion that links imaginatively to Dylan’s greatest songs, and, in the end, has the richness lacking in much of the singer-songwriter’s work of the past thirty years.

I liked best Dylan’s detailed account of the of the ’60s and the folk scene, maybe because I remember much of this myself, from the vantage of a high school kid going down to the village to see Len Chandler and Richie Havens, both of whom make significant appearances here. Indeed my teenage years were filled with concerts and records by Tom Paxton, Tim Hardin and Hamilton Camp, Richard and Mimi Farina, Leonard Cohen, Joan Baez and Judy Collins. But also, as of 1968, Randy Newman, Van Dykes Parks, and Tiny Tim (whom Dylan writes about with warmth, suggesting a perhaps unexpected affinity). I have a vivid memory of seeing Bill Cosby at the Bitter End on Bleecker, just about the time his first album came out with his signature routine about staring in the mirror one day and discovering “little tiny hairs growing out my face.”

My favorite singer/songwriter from this time, apart from Dylan and Newman, was Phil Ochs, who is never mentioned in his comrade’s chronicle, which is a shame, given their connection in time, place, and approach; but Dylan is more interested in charting his connection to his imaginary generational comrades, Ricky Nelson and Frank Sinatra, Jr.—and indeed he plays the oddness of this with great effect.

I still recall when my brother (four years older than me and hanging out in the Village) put on that first Dylan disk in 1962—and I thought what is that sound, that rawness, that blast of full-bodied force. Dylan’s voice embodied the opposite of the sweet-toned, in-tune pop and folk singers; indeed it was a sort of voice brute or even voice concréte—a rejection of polish or finish, a virtuosic, rhythmically powerful merging of the ugly, the raw and the untrained. This was what McLuhan called “hot” and it blasted out against the “cool” culture of the early ’60s like a bucking bronco in a record shop. Dylan’s howl, his willfully non-pretty singing, used the noise of the voice as the ground against which his words figured. In retrospect, I’d say the closest correlate to this was the Mississippi Delta blues of Charley Patton (about whom Dylan has written a recent song), even more than Robert Johnson, who is discussed in detail in Chronicles. It makes sense that Dylan gives so much credit to Dave van Ronk, for he got there, or near there, first.

Around the time I heard Dylan wailing “I’d DO anyTHING in this GOD Almighty WORLD if you JUST let me FOLLOW you down” from the room next door, I also discovered Al Jolson, buying six compilation LPs on the boardwalk in Atlantic, where I had gone, with my sister and grandmother, just after my father’s heart attack. My brother was quick to note that Dylan was the opposite of Jolson (and some of the other Broadway singers I liked at the time, in particular, much to my brother’s disapproval, Sammy Davis, Jr.); but perhaps Jolson and Dylan have more in common than meets the eye. Many of the dilemmas of The Jazz Singer, in terms of mimicry and identity, are also dilemmas for Dylan, who, after all, stops his narrative to discuss, in detail, his invention of the name Bob Dylan, just as Asa Yoelson tells us how he became Al Jolson. Behind Dylan is not just Woody Guthrie but the Gershwins, Irving Berlin, E. Y. Harburg, and Oscar Hammerstein, II. Dylan comes about as close to saying this as he can, noting his always happy, never ambivalent, identification as a commercial song writer. What brings this all back home, though, is his acknowledgement of the famous early ’60s New York production of Kurt Weill and Bertholt Brecht’s _Threepenny Opera_as a galvanizing experience.

We are all Brechtians now.

Early Dylan was blisteringly unsentimental; his voice projected, paradoxically, a convoluted, tangled, introversion, a voice that had drawn on the cacophony of free jazz and that symbolized the ascent of the rough over the smooth. All this would change in 1969 with the introduction of Dylan’s new voice on Nashville Skyline, a voice he perfected in the parodic bliss of his most significant self-reinvention, Self-Portrait (which, given his interest in Rimbaud, could be more accurately titled, portrait of self as an other). Dylan grouses throughout Chronicles that he should not be taken at his word, that he is not, and could never be, authentic; but the narrative (in the book and in his music) is conflicted and ambiguous. On the one hand, Dylan portrays himself as the Brechtian performer, as an entertainer playing a role, or rather, as playing the role of an entertainer who plays roles. On the other hand, Dylan allegorizes his changes as a search for his “real” self, that is, a journey of self-discovery. Does Dylan betray folk music at Newport or is he being true to himself? Or is he being true to folk music by being true to himself?

“There must be some way out of here….”

Chronicles reveals Dylan to be in the sway of what Susan Schultz calls “a poetics of impasse”: poetry that is stopped in its own tracks, hoisted on its own petards. Among her examples are Hart Crane, who is the second-wave modernist poet that bears the closest resemblance to Dylan, and Laura Riding, who stopped writing poetry in the late 1930s from a sense that her own artifice was in conflict with her desire for truthfulness.

From the first, Dylan hitched his star to a practice of nonconformity; but along the way he began to take nonconformity as something literal rather than metaphoric; the parodic lost its joissance and became (in his own perception) a shell game. The problem is not that Dylan ever betrayed his listeners or his genres, quite the contrary, but that he came to feel, like the Lon Chaney figure in the “False Face” episode of Way Out (a 1961 TV show), that his roles and masks were not only impossible to shake off but that that they have taken possession of him.

In his memoir, Dylan is at pains to come across not as an iconoclast (’cept if the icon he wants to smash is “Bob Dylan”: he is good at that) but as an autodidact. Being a proud autodidact is crucial to Dylan’s self-presentation and he uses this identity as cudgel to explain his intentional and disconcerting avoidance of any connection (much less commitment) to the social grounding of his early songs. ’cordin’ to Bob, it’s all ’xplained by the Civil War, based on some mid-nineteenth century newspapers he pored over in the library in the early ’60s. This ain’t history (any more than a memoir is history), but history used as a veil for an ahistorical, occasionally apocalyptic worldview. When, toward the end of the chronicle, our anti-hero insists that Master of War Hall o’ Famer Barry Goldwater is the politician he most admires, you know that this incarnation of Bob Dylan is not one of Woody’s people, even if we are deep in tall tale country. When you turn the page, it should no longer be a surprise, yet somehow it always is, in this looking glass world, that Dylan is awe-struck (in his own wry way) with Archibald MacLeish but finds James Joyce too intellectually challenging to bother with.

Indeed, the Dylan of Chronicles is not so much apolitical as anti-political, because much of the effort of the book is directed at throwing the overly curious off the trail of the “true” person behind the songs. Moment to moment, the point-of-view of the writing appears disconcertingly inside the mind’s eye of the narrator. Dylan practices his phenomenology as shell game: even his solipsism is a kind of peek-a-boo charade. Because he allows himself almost no critical distance, it can feel as if the memoirist is offering himself as patient, etherized on the table. Few readers will resist making their own diagnoses, at least until they find themselves inside a carefully laid trap, designed to shortcircuit just such arm-chair analysis (“it ain’t me babe”). With his uncanny synthesis of vivid serial anecdotes and an unreliable narrator, Dylan is able, quite effectively, to counter expectations, characterization, and the sort of clichés for which he has such a visceral disgust.

Like early T.S. Eliot and Allen Ginsberg, both mentioned with appreciation in Chronicles, Dylan’s early work is redolent with Adolescent Sublime. Yet Chronicles, written by a man in his sixties, is as much a work of Adolescent Sublime as is “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Like a Rolling Stone.” In those songs, and others of that moment, Dylan echoes the reversals so prominent in one of Whitman’s greatest poems, and certainly Whitman’s most dystopian work, “Respondez”:

Let that which stood in front go behind! and let that which was behind advance to the front and speak…

Let none be pointed toward his destination! (Say! do you know your destination?)

Perhaps then the moral of the story can also be found in “Respondez”:

Let the reflections of the things of the world be studied in mirrors! let the things themselves still continue unstudied!…

Let the heart of the young man still exile itself from the heart of the old man! and let the heart of the old man be exiled from that of the young man!…

Bob, we love you. Grow up!

Nenhum Comentário!