Thursday, May 9, I picked up Bob Creeley at the airport. He exited the wrong way but I spotted him on time and called to him: Bob! He kissed me twice. João, my seventeen year-old son, was there with me. We got in the van of the US Consulate and he began to talk. He and I both nervous. He began to speak, he spoke, things I didn’t understand very well. I began to notice he liked to speak and I confirmed that later—speech as a kind of permanent introspective and creative monologue, chewing his words as if speaking was a way of seeing for him, who was blind in one eye. I drew his attention to the Tietê River during the trip from Guarulhos to the downtown of São Paulo. A dead river, with herons on its banks, strangely so. He commented, in passing, regarding the Nobel Prize that was awarded to Derek Walcott, some days before: “political demagoguery with no relation to good poetry.” After dropping off his luggage at the Bourbon Hotel on Av. Dr. Vieira de Carvalho, we went to my place, “amazing place,” in his kind words. Creeley, a man in his seventies, appeared to be 55 instead. His vitality was enviable. When she arrived home after picking up Bruna from school, Darly, my wife, was nervous: she was in front of a legend we had often read together. Bruna kissed him. After having a few drinks, we went out and I took some pictures of him in front of our building, an old building from 1955, in Rua Dr. Brasílio Machado; at that moment, Néstor Perlongher, who also lived in that street, was passing by. I introduced them and he exchanged a few words with him in Spanglish, because he had lived in the Canary Islands and spoke a few words of Spanish.

Creeley and Bruna Bonvicino

At home, still that evening, he explained to me some of his poems because I was then translating what would become the book A UM (1997). Mrs. Curley, “the poor Irish woman” of his childhood in the poem “Epic”—his epic to Milton, he said, a remembrance. He didn’t know anymore what he had meant by the word wit in the poem “For WCW.” He looked it up in Webster’s and we still didn’t get anywhere. Then he talked about “Focus”—a window and its frame and a plant in the middle: Mondrian. My (dubious) translation into Portuguese goes: “Retalhos do céu/ cinza linhas// das árvores/ recorta a// planta incli-/ nada ao meio.” Creeley’s poetry always seeks concrete situations, deadlocks, etc., a poetry, to make use of a cliché, of life and of words in words. Or, as Charles Altieri has pointed out in an essay, “In Creeley, themes disseminate rather than gather, but the project is not a Derridean one. Creeley wants to replace the conventional symbolic space that, as in jazz, invites variations and at once gathers and disperses energies, resonances. Or he summarizes this dispersing interplay of past themes, memories, and several levels of particulars.” As the sun was setting, we translated together some poems by Leminski into English and two of my own for the future anthology Nothing the Sun Could Not Explain. I would do the literal version and he the poetic one, the paper on his knees and the pen in his hand, excited, in good spirits, already a bit tipsy, improvising freely, perhaps in the style of Mile Davis or John Coltrane who were his friends from the 1950s on. At that point he told me he knew the Italian parents of Michael Palmer (coeditor of the anthology) and that he had met him when Palmer was twenty and lived in a New York hotel (where his father was the manager, Mr. Palmerini) and would take him to performances by Davis and Coltrane in the Village.

At night, in the Bourbon Hotel, he was interviewed by Rogério Pacheco Jordão from Jornal da Tarde. An old city center, “dangerous,” as he put it, with whores and crack addicts. I don’t remember what poem we read together out loud only for the two of us while we waited for the journalist. Jerusa Pires Ferreira e Boris Schnaiderman came a bit later. Creeley spoke of his fascination with Chinese characters, which he always reimagined mentally in English in his poems. He spoke of the words house, window, car, of their sounds, which interested him. Pacheco Jordão asked him about his poem “Ever Since Hitler” and he responded, “a painful poem, and now with the Bosnian War, another Hitlerian war.”

The next day, Friday, May 10, in the morning we did a reading of poems at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica, which was energizing, at least for the two of us. We read seven texts in Portuguese/English. Earlier, when he had came into the room, he ahd written on the blackboard: “multiculturalism” and the web address of the Electronic Poetry Center, where new American poets were featured, especially the Language Poets, whom he admired. A phrase that struck me was “American poetry was renovated, in this century, by a series of non-native speakers of English or by bilingual ones.” He told us the native language of William Carlos Williams had been Spanish—his mother was Puerto Rican. Lorine Niedecker’s mother tonge was German, etc. He was asked about the relationship between poetry and new media. Clarity and speed were the qualities he stressed about the Internet: “E-mail makes things simultaneous and fast—I love it.” Haroldo de Campos insisted spontaneously on denouncing Harold Bloom’s conservatism as detrimental to contemporary literature and he asked Creeley’s opinion on the subject (he later also told me in private that he thought Creeley was a “relenting poet”). Creeley, somewhat uninterested said that Bloom’s point of departure was the concept of symbol in literature and that he did not analyze objects and that he, Creeley, despised critics in general. He made an exception with Marjorie Perloff, saying, on the other hand, that she was hated by many others. And he also revealed that in elementary and secondary school he had been in the same class with John Ashbery, Bloom’s favorite.

We had lunch with Duda Machado in the restaurant Nabuco. He loved the flounder. (In the evening, at a dinner party at my place, he said me he had told his wife Penelope about it on the phone: Delicious flounder.) We walked towards the Pacaembu Stadium. At some point, a wide rough wall, full of graffiti entangled in lush ivy. A huge canvas. I thought of Frank Lloyd Wright. I wanted to take a picture of “that,” but I had no camera. Multiculturalism: the encounter of various languages and dictions, against ethnocentrism, he said. Several beggars approached us on our way from Nabuco to the Pacaembu Stadium asking for money. He would give them coins or greeted them politely taking off his hat. He lent me his Borsalino hat and went to the hotel to rest; later that evening I was photographed with that Borsalino hat at a dinner party in my house attended by Guto Lacaz, Duda Machado, Aurora Bernardini, Carmen e Haroldo de Campos, Jerusa e Boris. After the dinner, Darly and I took him to his hotel. At Rua Baroneza de Itu, he spotted a garbage truck going from building to building collecting the bags that the workers hurled into the grinder. He began to “chew” the word crunch, which we used the next day to begin a renga entitled “Together.” published in 1996. I did the first stanza and he the second: “at late evening/ lights/ red yellow/ crunch/ the trash/ on the truck” (RB) and “Under the overhang/ the other road/ look up there/ black night sounding/ fearful of those/ still out there” (RC). Two months later, he wrote me: “I’m much looking forward to seeing the renga, which Vincent Katz tells me is very handsome.”

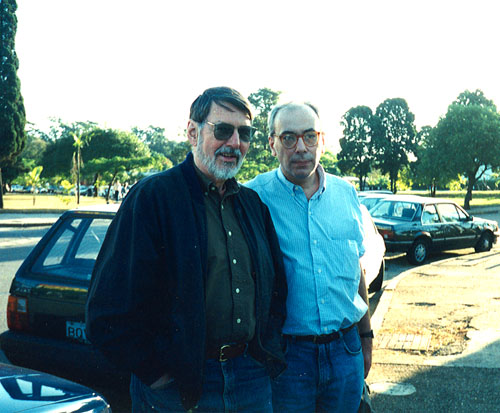

On Saturday, Creeley and I visited the Casa das Rosas, directed by José Roberto Aguilar. The first thing Creeley did was smell the roses! He seemed more interested in the roses than in the holdings. He asked me their names and wanted to know if they were native, etc. I told him the house was designed and built by Ramos Azevedo, a famous architect from São Paulo, who made the garden especially for his wife, a rose collector. He loved Ibirapuera Park, where we went on Sunday, May 12, with its huge open spaces, its plants and trees, and the MAM building, the collection. He told me his son William was studying, at that very moment, the work of Oscar Niemeyer. He observed that the concrete used as material and the monumental scale of the Memorial da América Latina were the exact opposite of the type of architecture of the New England houses were he grew up and had formed his aesthetic sensibility.

Creeley and Régis Bonvicino

The extraordinary reading at the Memorial da América Latina, on May 13, organized by José Miguel Wisnik, featured 25 (!) people in the audience. Next to him, hearing him, I noticed he extracts, decants, gets unknown sounds from words, sounds that are, so to speak, inaudible even to the sharpest ears. Voice as an instrument. At night we did another reading, this time at the daily Folha de São Paulo, in an auditorium with more people and more debate, despite the interesting interventions by Wisnik at the Memorial.

He told me, almost in secret, almost as he was leaving, that Allen Ginsberg had serious heart problems and had no money for an expensive treatment, and that he made ends meet with donations from his friends. We also talked about the poetry of Gregory Corso, another Beat poet connected to Creeley: and Bob, with his deep, introspective voice let out a stanza from “Bomb”: “There is a hell for bombs/ They’re there I see them there/ They sit in bits and sing songs/ mostly German songs/ and two very long American songs.” On May 14 he left to spend one day in Rio from where he would then go to Asunción, Paraguay.

Régis Bonvicino, August 1996.

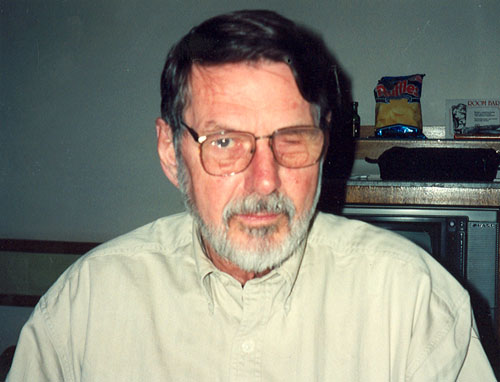

Creeley in his São Paulo Hotel room

Translation: Odile Cisneros

Nenhum Comentário!